The Timeless Appeal of Portrait Miniatures: Art, History, and Collectability

Portrait miniatures occupy a special place in art history, admired for their fine detail and delicate craftsmanship. These tiny, yet exquisite works of art were created using a variety of materials, including watercolours, gouache, graphite, and enamels, often painted on surfaces such as copper, vellum, cardboard, and later, ivory. These miniatures were not confined to traditional frames—they were also incorporated into lockets, jewellery, and even decorative items like snuff boxes, adding to their versatility and charm.

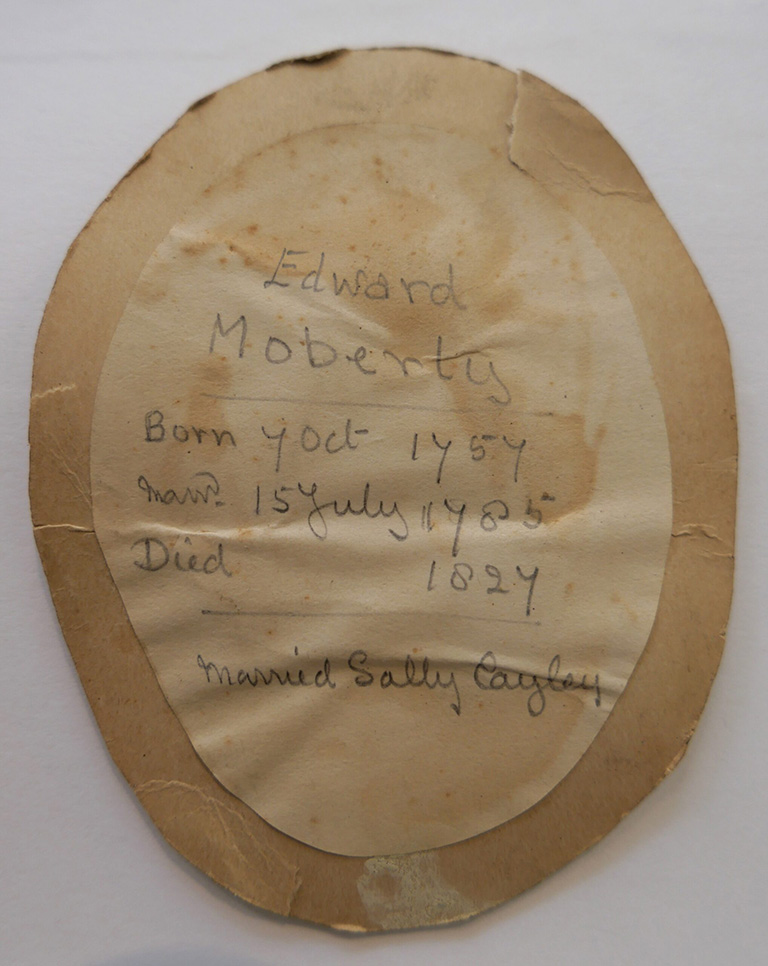

Before the advent of photography, portrait miniatures were a popular way to keep images of loved ones close at hand. Dating back to the Renaissance, the art form reached its peak in the 18th century, when they became more accessible to the emerging middle class, no longer reserved solely for the aristocracy. These miniature portraits were often commissioned to commemorate loved ones before a long absence, such as a soldier leaving for war, or a daughter marrying into a new family. The treatment and case study below, depict a young Edward Moberly (1757-1827) and an even younger Sally Cayley (born 1764) who married on July 15th, 1785.

Ivory became the preferred surface for miniatures in the early 1700s, initially in Venice, before spreading across Europe to countries like England, Germany, and Holland due to its smooth texture and translucent quality, which made it ideal for capturing lifelike skin tones. While vellum remained in use until the mid-19th century, ivory’s ability to reflect natural flesh tones became a favourite among artists. Miniaturists skilfully layered paint on the waxy surface of ivory to enhance the illusion of glowing skin, elevating their craft to a new level of realism.

To preserve the natural luminosity of the ivory, adhesives were selectively applied only to the edges of the support. The choice of backing material significantly impacted the final appearance of the painting. Silver foil, or paillons, were sometimes placed beneath the ivory to enhance its brightness, a technique more common on the Continent than in England.

Given the limited size of elephant tusks, which restricted the maximum width of an ivory sheet to around 16 cm, artists often employed creative solutions for larger compositions. They would attach small ivory sheets to larger cards or wooden panels, using the ivory only in critical areas like faces and hands, while the borders could be evened out with a white base coat. This clever technique allowed them to maximise the visual impact of the ivory, maintaining its luminous quality where it mattered most.

The enduring fascination with portrait miniatures lies in their ability to capture not just the likeness, but the spirit of an era, making them treasured pieces of both personal and cultural history.

Case study and conservation treatment: Treatment of a Pair of framed portrait miniatures on ivory of Edward Moberly (1757-1827) and Sally Cayley (born 1764).

Recently, a pair of miniatures on ivory came to our studio, where they were restored by our team with techniques that reduced visual disturbances, such as mould, paint loses, mould spores and surface dirt to ensure its future preservation. Both portraits of maximum diameter 8.5cm had their details in the back and were framed in matching lacquer and gilt frames. These frames were too big for the objects with the original concave glazing being substituted for two hand cut plastic sheets.

Background – The portraits represent Edward Moberly a merchant in St Petersburg, born in 1759 at Knutsford, Cheshire, England and Sarah Cayle (daughter of the Consul-General) who married on the 15th of July 1785. The family left St Petersburg during the Russo-Swedish War (1788–1790) and decided to return to Ham, England. In 1814, once things seemed safer, Edward and Sarah Moberly returned to Russia, where Edward became the British Consul in St Petersburg.

Process – The first step was to remove the miniatures from their frames, clean and disinfect the fine threads of mould on the surface and other pollutants. Interestingly, mould grows in climates where relative humidity is higher than 65 per cent, which means most households.

The miniatures were then first removed from their cardboard linings. Early ivory sheets were about a millimetre thick, but by 1780, thinner sheets were more common, requiring backing paper for stability. Ivory tends to contract slightly with time and when glued to paper, such as in this case, the ivory sheet deformed in a concave manner which caused cracking. To eliminate stresses and the risk of further cracking, the ivory sheet was separated from its backing paper by our paper conservation specialist.

After surface cleaning with pH modified solutions, we allowed it to fully dry under soft weights to prevent further distortions on the support and our paper conservator carefully retouched with specialist pigments all the main areas of concern and loses.

Finally, the miniatures which were smaller than the frame, were first mounted on a conservation bespoke oval mountboard to prevent them from unrequired movements and framed hem respecting their current and prevent further damage to the ivory sheet. Then, all the plastic glazing was replaced for a 99% UV filter glazing with Melinex inserted into the backing.

These charming 18th-century pieces had significant sentimental value to our client. We wanted to honour that by stabilising the miniatures, improving the glazing and mounting, thus allowing the full details of the artwork to be revived.

Caring for your Portrait Miniatures: Key Considerations

Humidity and Temperature Control

Ivory miniatures, like works on paper, are highly sensitive to environmental changes. Excess humidity can lead to mould growth, while overly dry conditions can cause parchment to become brittle and ivory to crack. To prevent such damage, it is recommended to maintain relative humidity below 55% and a stable temperature around 15°C.

Preventing Colour Fading

Many miniatures were painted using animal or vegetable-based pigments, which are highly sensitive to light and prone to irreversible fading. Once damaged, it is nearly impossible to restore these areas to their original state. To protect your miniatures, always keep them away from strong light exposure.

Mounting and Glazing

Miniatures were traditionally covered with convex glass to prevent them from sticking to the painting. However, this glass can retain high levels of moisture forming on the inside. If this occurs, the glass should be replaced with a conservation UV glazing and the edges sealed with paper to prevent dirt from entering.

How we can help

Our team of conservators specialises in treating works on paper, parchment, and ivory. We offer services to clean and stabilise damaged materials, and if needed, we can replace missing sections of ivory and parchment with modern substitutes. We also provide framing solutions to protect your miniature further.

If you’re concerned about your miniature’s condition, please feel free to contact our team at info@manleyrestoration.com for expert advice and assistance.